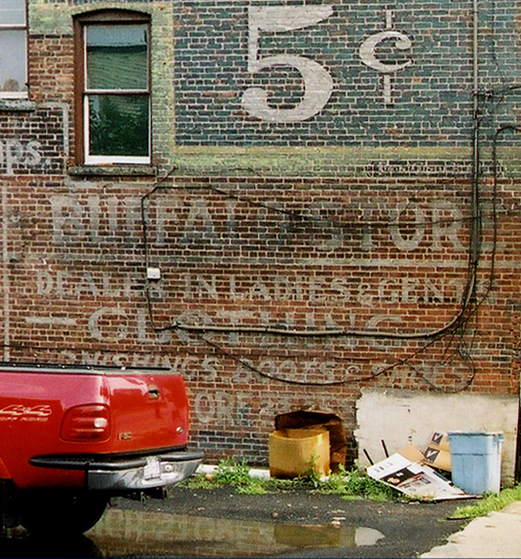

But what of the mysterious sign whose letters still faintly trace the words "Buffalo Store"?

The story goes that the "Buffalo Store" concept dates back to the days of the Erie Canal, when canal boat passengers first exposed back country hamlets to big city styles. A "Buffalo Store" professed to deal in fashions as sophisticated as those worn by the "ladies and gents" on Delaware Avenue or in Niagara Square. Although Schenectady was far from a hamlet, the name "Buffalo Store" carried a far more stylish cachet than "dry goods store", the period's generic term for an establishment that sold fabric and clothes.

In 1930, this building at 412 Broadway was home to both Benjamin Miller's clothing store and the Miller family. Benjamin Miller and his wife Ida had emigrated from Russia just after the turn of the century; his mother Fannie followed in 1920. The Millers rented the remainder of their house to five African-Americans, four of whom were orchestra musicians.

412 Broadway was in fact a social dividing line. To the north, Broadway had virtually all white residents, fully half recent immigrants from such European countries as Germany, Poland, Russia, Italy, and Lithuania. However, the neighborhood demographic altered greatly to the south.