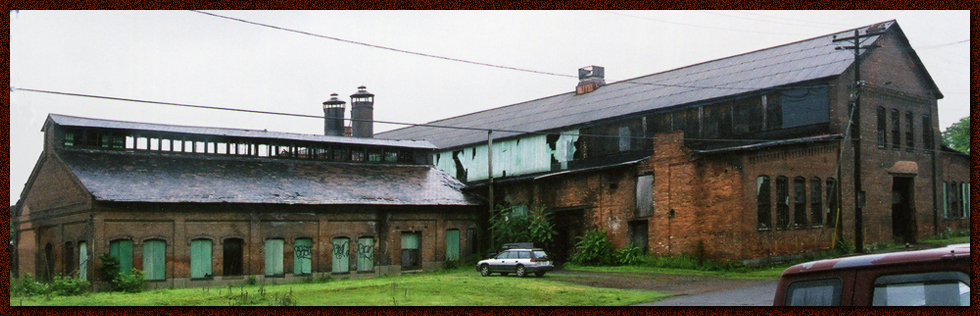

In late April 2008, Governor David Paterson came to the Rensselaer Works to announce that it would become the home of an ecological center, to include the monitoring hub of a $200 million sensor network covering 315 miles of the Hudson River.

The center would incorporate a restored Merchant Mill and other early buildings, as well as a municipal campus with bike paths, picnic grounds and docks. As the Albany Times-Union wrote," the future for the Rensselaer Iron Works seemed secure".

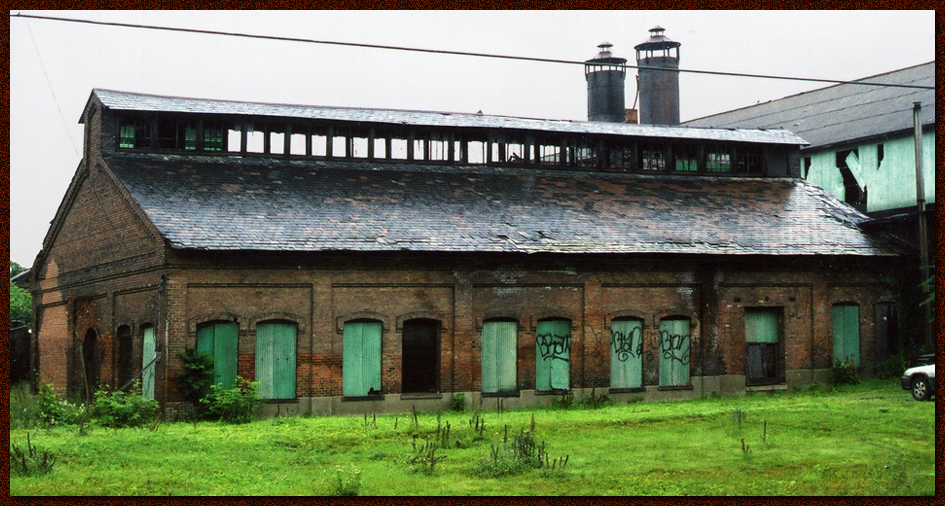

But in the late afternoon of May 25, 2008, the arsonists finally hit the trifecta. A blaze that drew firefighters from Troy, Albany, and Watervliet burned through the forge and a section at the rear of the Merchant Mill. Firefighters were unable to fight the fire from inside because of fears that the main gallery's bridge crane would collapse.

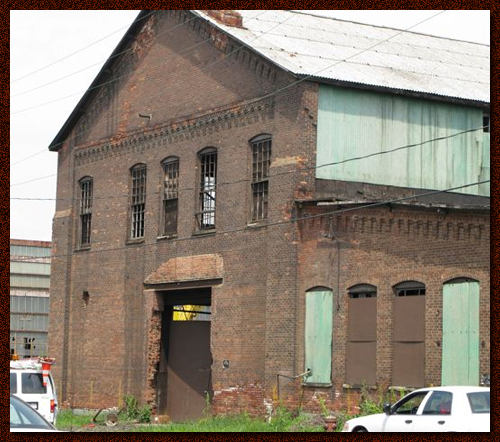

Many Trojans believed that much of the Merchant Mill could be saved (left). However, although the 125 year old iron trusses resisted strenuously (below left), the entire building was demolished within days.

Today, the Rensselaer Iron Works is survived chiefly by its machinery. Ironically, this includes the bridge crane (bottom), which may be re-erected as an outdoor display. It is scant consolation that the surviving small buildings will be combined with new structures in the Hudson River monitoring center project.

CLICK HERE FOR OLEK SKOTNICKI'S ON-SCENE FIRE PHOTOS

RENSSELAER ROLLING MILL B&W PHOTOS FROM LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, HAES

SITE, BUILDING EXTERIOR, DEMOLITION, AND SURVIVING MACHINERY PHOTOS BY HOWARD OHLHOUS AND POST-FIRE PHOTOS COURTESY OF JIM DE SEVE

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE